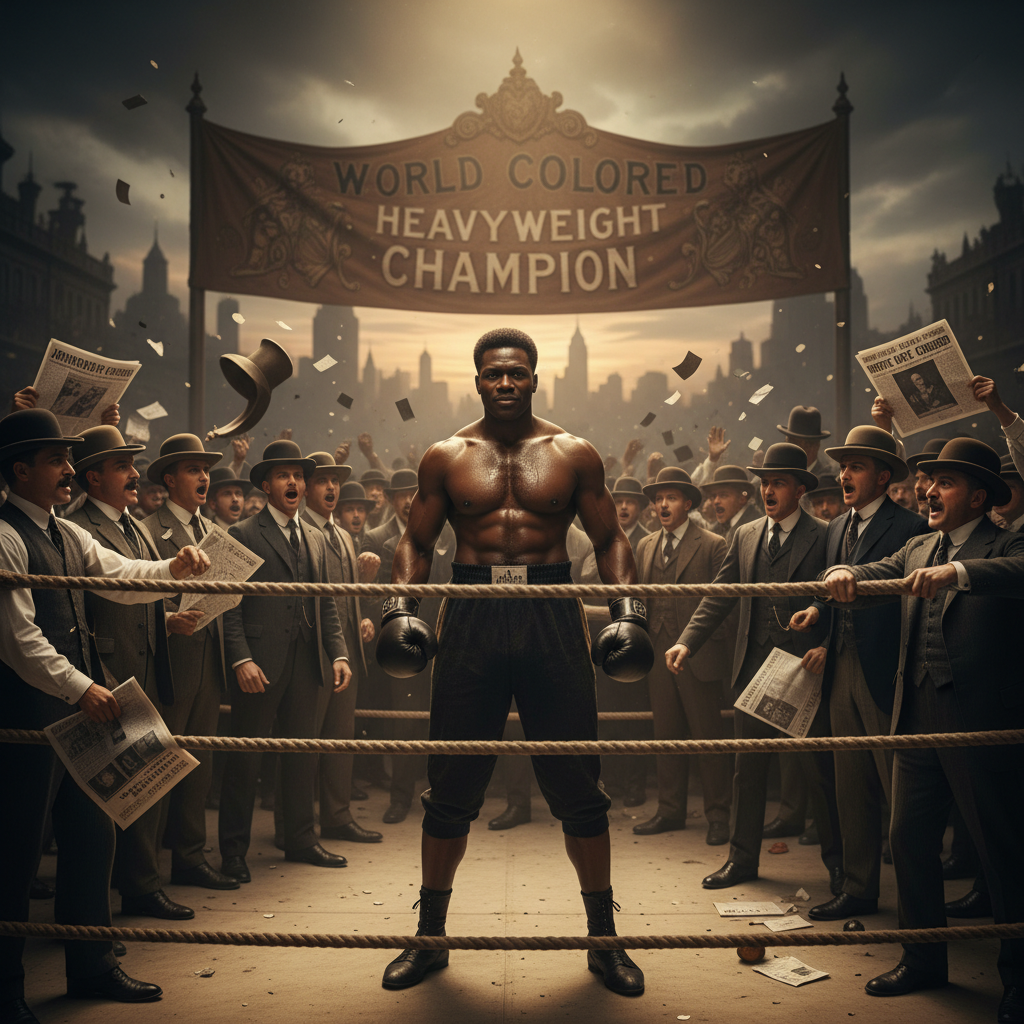

In the annals of sports history, few figures loom as large—or as controversially—as Jack Johnson. Born in Galveston, Texas, in 1878, Johnson rose from the poverty of the post-Reconstruction South to become the first African American World Heavyweight Boxing Champion. However, his significance extends far beyond the ropes of the boxing ring. Johnson was not merely a fighter; he was a cultural lightning rod who forced America to confront its deeply entrenched racial prejudices during the height of the Jim Crow era.

Before Johnson, the heavyweight championship was considered the exclusive property of the white race. It was viewed not just as a sports title, but as a symbol of racial superiority. While black fighters were allowed to compete in lower weight classes, the heavyweight crown was guarded by an unwritten rule known as the color line. Champions like John L. Sullivan and James J. Jeffries openly refused to fight black contenders, claiming that the title represented the pinnacle of white masculinity.

Breaking the Color Line

Jack Johnson’s journey to the title was a masterclass in persistence and psychological warfare. Possessing a defensive style that was years ahead of his time, Johnson would often taunt his opponents while effortlessly slipping their punches. He spent years chasing the reigning champion, Tommy Burns, around the globe, goading him in the press and at ringside. It wasn’t until 1908, in Sydney, Australia, that Burns finally agreed to the fight, largely due to a guaranteed purse of $30,000—an astronomical sum for the time.

The fight against Burns was a dismantling. Johnson didn’t just win; he humiliated the champion. He mocked Burns throughout the bout, smiling for the cameras and conversing with ringside spectators while punishing his opponent. When the police finally stopped the fight in the 14th round to save Burns from further punishment, the world of boxing was turned upside down. For the first time in history, a black man held the most prestigious title in sports, sparking a wave of anxiety across white America.

The Search for the Great White Hope

The reaction to Johnson’s victory was immediate and visceral. The press and the public clamored for a “Great White Hope” to reclaim the title and restore the perceived natural order. This desperation led to the unretirement of undefeated former champion James J. Jeffries. Jeffries, who had previously refused to fight Johnson, was coaxed back into the ring with the specific mandate to “wipe that golden smile off Jack Johnson’s face.”

The ensuing bout, held on July 4, 1910, in Reno, Nevada, was billed as the “Fight of the Century.” It was more than a boxing match; it was a proxy war for racial ideology. The atmosphere was thick with racial tension, with bands playing “All Coons Look Alike to Me” and the crowd hurling vitriol at the champion. Yet, Johnson remained remarkably calm, a trait that would define his legacy as the original sports villain.

Inside the ring, Johnson was surgical. He neutralized Jeffries’ power and picked him apart with precision strikes. By the 15th round, the outcome was undeniable. Johnson knocked Jeffries down—something that had never happened in the former champion’s career. Jeffries’ corner threw in the towel to prevent a knockout, cementing Johnson’s status as the undisputed king of the heavyweights. The aftermath was tragic: race riots erupted in dozens of cities across the United States, resulting in numerous deaths and revealing the deep fissures in American society.

The Lifestyle of a Rebel

What made Jack Johnson truly dangerous to the establishment was not just that he won, but how he lived. He refused to be humble or apologetic. At a time when African Americans were expected to be deferential, Johnson was flamboyant, arrogant, and unapologetically wealthy. He drove fast, custom-made luxury cars, wore tailored suits, and drank champagne. He lived life on his own terms, effectively creating the blueprint for the modern athlete-celebrity.

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of Johnson’s life was his relationships with white women. In the early 20th century, interracial relationships were not only socially taboo but often illegal. Johnson openly dated and married white women, parading them in public in a direct challenge to the social mores of the time. This behavior infuriated the public and the government more than his boxing victories ever could.

The media played a crucial role in crafting Johnson as a global villain. Newspapers caricatured him using racist tropes, depicting him as a brute with animalistic urges. Yet, Johnson leaned into the villain persona. He understood the economics of controversy long before Muhammad Ali or Floyd Mayweather. He knew that people would pay to see him lose, and he capitalized on that hatred to become one of the wealthiest athletes of his generation.

Legal Persecution and Exile

Unable to defeat him in the ring, the establishment turned to the legal system. In 1912, Johnson was arrested under the Mann Act, a federal law designed to prevent human trafficking for “immoral purposes.” The law was weaponized against Johnson, using his consensual relationship with his white girlfriend (who later became his wife) as the basis for prosecution. It was a racially motivated witch hunt intended to destroy his reputation and freedom.

Convicted by an all-white jury in 1913, Johnson was sentenced to a year and a day in prison. Rather than serve time for a crime he didn’t commit, he fled the country. For seven years, Johnson lived in exile in Europe and South America, defending his title sporadically and living as a fugitive. It was a period of wandering, where the man who had conquered the world was forced to live on its fringes.

In 1915, an aging and out-of-shape Johnson finally lost his title to Jess Willard in Havana, Cuba. The fight lasted 26 rounds under the blistering sun. Controversy still surrounds the bout, with Johnson later claiming he threw the fight in exchange for leniency from the U.S. government, though this was never proven. Regardless of the circumstances, the reign of the Galveston Giant had come to an end.

A Complicated Legacy

Jack Johnson eventually returned to the United States in 1920 and served his prison sentence. He continued to fight well into his 60s, though never for the title. He died in a car crash in 1946, driving with the same reckless speed that had defined his life. For decades, his name was spoken in hushed tones, often used as a cautionary tale for black athletes to stay “in their place.”

However, history has since re-evaluated Johnson. He is now recognized as a pioneer who paved the way for icons like Joe Louis and Muhammad Ali. Ali, in particular, often cited Johnson as a major inspiration, admiring his refusal to compromise his identity for the comfort of others. Johnson was the original archetype of the anti-hero in sports—a man who realized that being the villain paid better than being the hero, provided you could back it up.

In 2018, more than a century after his conviction, Jack Johnson was posthumously pardoned, officially clearing his name of the racially motivated charges that had tarnished his legacy. Today, he stands not just as a great boxer, but as a symbol of defiance. He forced the world to look at a black man not as a servant, but as a champion, a master of his craft, and a man who would rather be hated for who he was than loved for who he was forced to be.