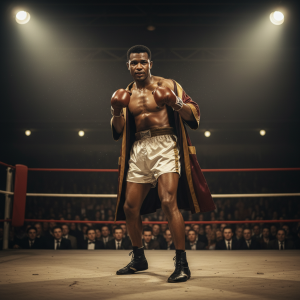

Before Muhammad Ali, boxing was primarily defined by the grim, smoky atmosphere of arenas and the straightforward brutality of two men trading punches. While champions like Joe Louis and Rocky Marciano were respected for their power and resilience, the sport lacked a transcendent narrative that could capture the imagination of the entire world. Muhammad Ali changed this forever. He did not merely box; he performed. By fusing elite athleticism with a charismatic persona, Ali transformed the boxing ring into a stage for global theater, setting a precedent for modern sports entertainment that remains unmatched to this day.

The transformation began with the persona of Cassius Clay, the brash young Olympian from Louisville. Unlike the stoic fighters of the past who let their managers do the talking, Clay took control of the microphone. He understood early on that in the age of television, attention was currency. By declaring himself "The Greatest" before he had even earned the title, he created a storyline that demanded resolution. Audiences tuned in not just to see a fight, but to see if the arrogant young poet would be silenced or if he would back up his outrageous claims.

The Louisville Lip: Poetry in Motion

Ali introduced a rhythmic cadence to sports promotion that was entirely unprecedented. He was, in many ways, a precursor to hip-hop culture, utilizing rhyme and flow to dismantle his opponents mentally before physically engaging them. His predictions of the round in which his opponent would fall were not just guesses; they were scripts. When he recited, "Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee," he was providing the marketing tagline for his own brand, simplifying complex boxing dynamics into a digestible, memorable ethos that transcended language barriers.

This theatrical approach served a dual purpose. First, it sold tickets. People paid to see him lose just as often as they paid to see him win. Second, it waged psychological warfare. By the time Sonny Liston or George Foreman stepped into the ring, they were often already fighting the myth of Ali rather than the man himself. This psychological edge was a key component of his theatricality, turning the pre-fight weigh-ins and press conferences into events that were often as entertaining as the bouts themselves.

Politics and Religion as High Stakes Drama

True theater requires stakes higher than a paycheck or a belt, and Ali injected real-world tension into his career. By joining the Nation of Islam and changing his name from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali, he cast himself as a protagonist in the civil rights struggle. This was no longer just sport; it was a sociopolitical statement. His refusal to be drafted into the Vietnam War, famously stating, "I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong," elevated him from a sports star to a global symbol of defiance.

The three-year exile that followed his refusal to serve added a tragic act to his career arc. Stripped of his prime years, Ali became a martyr figure to the counterculture and a villain to the establishment. This polarization meant that when he finally returned to the ring, his fights were viewed through the lens of ideology. You weren’t just rooting for a boxer; you were rooting for a worldview. This depth of narrative is what turned his fights into must-watch television for billions, regardless of their interest in boxing.

The Rumble in the Jungle: The Ultimate Stage

Perhaps the zenith of Ali’s global theater was the Rumble in the Jungle in 1974. Held in Kinshasa, Zaire, the event was a masterclass in spectacle. Don King promoted it, but Ali directed the narrative. He positioned himself as the representative of Africa and the diaspora, painting George Foreman as the sullen, establishment brute. Ali spent weeks in Zaire prior to the fight, winning over the locals until the chant "Ali, bomaye!" (Ali, kill him!) echoed everywhere.

Inside the ring, Ali delivered a plot twist worthy of a Hollywood script. Facing a younger, stronger opponent expected to destroy him, Ali adopted the "Rope-a-Dope" strategy. To the uninitiated, it looked like he was losing, absorbing punishment against the ropes. However, it was a calculated dramatic tension. When he finally exploded off the ropes in the eighth round to knock Foreman out, it wasn’t just a victory; it was the climax of a perfectly paced drama, solidifying his legend as a tactical genius.

The Thrilla in Manila and the Cost of Glory

If Zaire was an adventure film, the Thrilla in Manila against Joe Frazier was a gritty war epic. This trilogy of fights showcased the darker side of Ali’s theatricality. His mockery of Frazier crossed personal lines, creating a genuine hatred that fueled the intensity of their encounters. The third fight in the Philippines pushed both men to the brink of death. It demonstrated that Ali’s theater was visceral and dangerous, proving that the blood spilled was real, which only heightened the audience’s emotional investment.

Ali’s ability to command the camera extended to his relationship with broadcasters, particularly Howard Cosell. Their verbal sparring matches became legendary, a traveling roadshow that brought humor and intellect to sports broadcasting. Ali realized that the media was not an enemy to be avoided but a partner to be danced with. He gave reporters soundbites that were ready-made for headlines, ensuring he dominated the news cycle constantly.

Legacy of the Showman

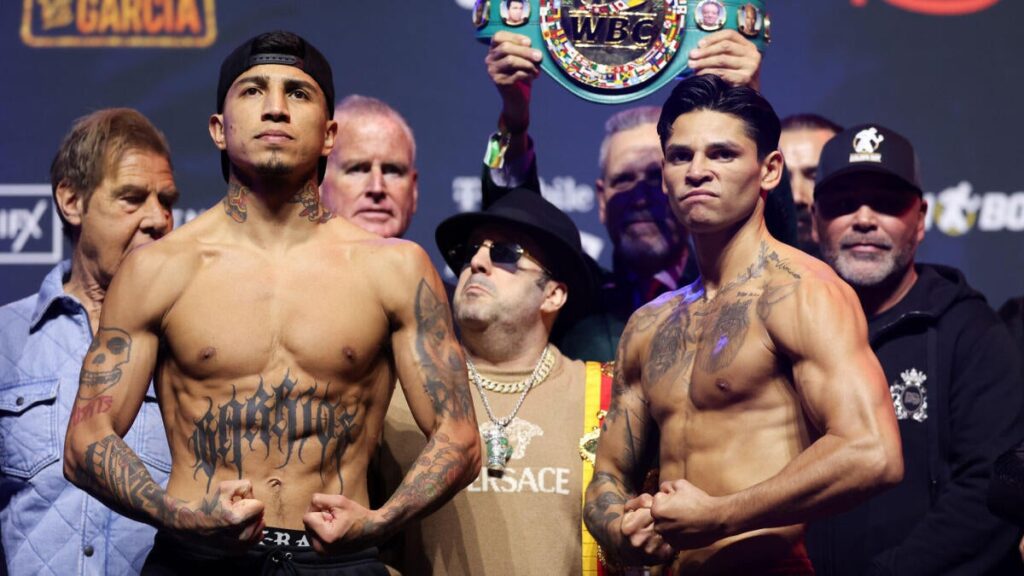

The blueprint Muhammad Ali created is evident in every corner of modern sports. We see his influence in the swagger of Conor McGregor, the business acumen of Floyd Mayweather, and the branding of Michael Jordan. Ali taught athletes that they could be their own promoters, that their personality was an asset as valuable as their physical talent. He pioneered the concept of the athlete as a global brand, capable of influencing culture, fashion, and politics.

- Self-Promotion: Ali proved that controversy creates cash and that silence is the enemy of revenue.

- Global Appeal: He was the first athlete to truly conquer the world stage, fighting in London, Frankfurt, Kinshasa, Manila, and Tokyo.

- Psychological Dominance: He showed that the battle is often won before the first bell rings.

- Moral Complexity: He demonstrated that taking a stand on social issues could enhance, rather than diminish, an athlete’s legacy.

Even in his later years, as Parkinson’s disease silenced the "Louisville Lip," Ali remained a master of theater. His lighting of the Olympic cauldron at the 1996 Atlanta Games was a moment of silent, trembling poignancy that moved the world to tears. It was the final act of a lifelong performance, transitioning from the brash warrior to the fragile, beloved elder statesman.

In conclusion, Muhammad Ali’s contribution to boxing goes far beyond his record of wins and losses. He took a sport confined to the back pages of newspapers and placed it on the front page of history. By weaving together race, religion, politics, and poetry, he turned the square circle into a global theater where the human drama played out in its most raw and electrifying form. He was, and remains, the greatest showman the sporting world has ever seen.